Encouraging people to donate to charitable causes is not an easy task. However, there are some interventions that make it easier.

Millions of people around the world have their most fundamental rights threatened every day. The terrible violence in Haiti, the deadly outbreak of hepatitis E in Sudan, and the war in Ukraine have led to some of the greatest humanitarian crises of our time.

The UN itself recognizes that governments alone are insufficient to protect human rights and ensure people’s well-being. According to the organization, volunteering and philanthropy by organizations and individuals are therefore crucial.

Where do we stand? According to the World Giving Index 2024, 35% of the global population donated money to charities during 2022 and 2023. In addition, 24% volunteered.

Among the most altruistic countries, Singapore stands out. In just two years, it has risen from 19th to third place in the global index of donor nations. This is due to the government’s various initiatives in response to the pandemic to encourage donations and volunteering among its population.

How can other countries follow suit? By applying behavioral science.

Numerous behavioral interventions have proven effective in encouraging people to be more charitable. In honor of International Charity Day, here are three recent examples with key lessons for significantly increasing fundraising.

Decide Today, Donate Tomorrow

With a concept reminiscent of the famous “Save More Tomorrow” intervention (Thaler & Benartzi, 2004), Andreoni and Serra-Garcia discovered that a person is more likely to contribute money to a cause if they first agree to donate and, instead of paying the money immediately, the donation is scheduled for a later time.

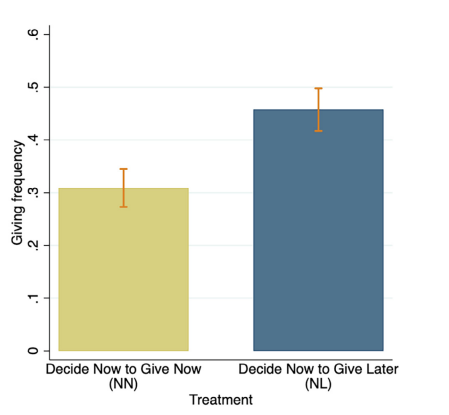

In one of their experiments, the control group was offered the opportunity to donate money (decide and pay) immediately (Decide Now to Give Now). This group faced a decision similar to the one proposed by donation requests we often encounter in everyday life, where we are asked to donate (pay) immediately.

In contrast, the treatment group was offered the opportunity to decide now but pay the following week (Decide Now to Give Later). The result? A 14 percentage point increase in the number of people willing to donate (or a 50% relative increase), as can be seen in the figure.

Why did this happen? According to the authors, the increase is explained by the fact that the decision to donate itself triggers a social reward (social or self-signaling), which later, at the time of the donation, resurfaces and is accompanied by the satisfaction generated by the act of giving (warm glow). Thus, the act of giving is a process with unique social gratifications, which can appear at different times.

The findings of this research open the door to interesting questions. For example, is one timeframe for disbursement more favorable than another? Further research is certainly needed.

The Identity Factor

Additionally, some studies have investigated the boost provided by the identity factor. Appealing to a particular facet of a person can be a good catalyst for recruiting donors.

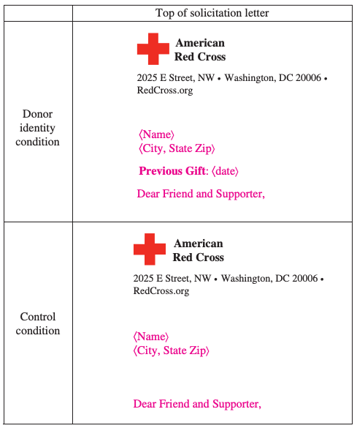

In one of their experiments, researchers Kessler and Milkman appealed to people’s identity as previous donors. To do so, they focused on people who had previously donated to the American Red Cross.

While the control group received a letter with a standard donation request, the treatment group received a personalized line reminding the recipient of their most recent contribution (see Figure 2).

The cost of adding a line of text? Zero. The benefit? A 20% increase in the likelihood of receiving a donation (6.33% in the control group and 7.59% in the treatment group). In a second experiment, also successful, participants’ identities as members of their community were appealed to.

Findings like these underscore the importance of designing campaigns that not only inform, but also resonate with people’s identities.

The Discomfort of Choosing

Along the same lines, common sense and some theories suggest that giving people options about how to help increases their sense of agency and fosters prosocial tendencies. However, sometimes choosing can be uncomfortable.

In one of their experiments, Brody and his colleagues divided their participants into three groups:

– Control group members received a standard donation request for Save the Children.

– The “What” group received a similar request, but with the option to specifically choose what to allocate the money for: nutritious food or hygiene items.

– Finally, the “Who” group was given the option to specifically choose who to allocate the money to: malnourished babies or orphans.

The researchers concluded that people with the option to choose what to donate (food or essentials) were more likely to donate (52.0%) than members of the control group (44.4%) and those with the freedom to choose whom to help with their donation (42.2%).

In other words, not all choices are valid. Being faced with the choice of “who to help” (for example, a child or a victim of trafficking) can generate discomfort and, in practice, paralyze the decision.

As the authors state, “While choosing between options can increase feelings of agency and satisfy individuals’ search for the warm glow (pleasure or satisfaction after helping others), facing a choice between two recipient populations can provoke a cold chill (discomfort in the decision), freezing the likelihood of donating.”

Every Drop Counts

These are just three examples of a broad and ever-growing area of research, full of learning and opportunities to capitalize on. By paying attention to evidence, organizations can increase audience and stakeholder engagement, prevent errors, and ultimately maximize the impact of their campaigns.

As the famous slogan says, every drop counts, and by combining the power of science with human generosity, we can make a real difference in the world.

Let’s bet on benefiScience!